From the History of Islam in the Right-Bank Middle Volga

10.11.2025

of Eurasia. Popularscience edition. Almaty, 2015.

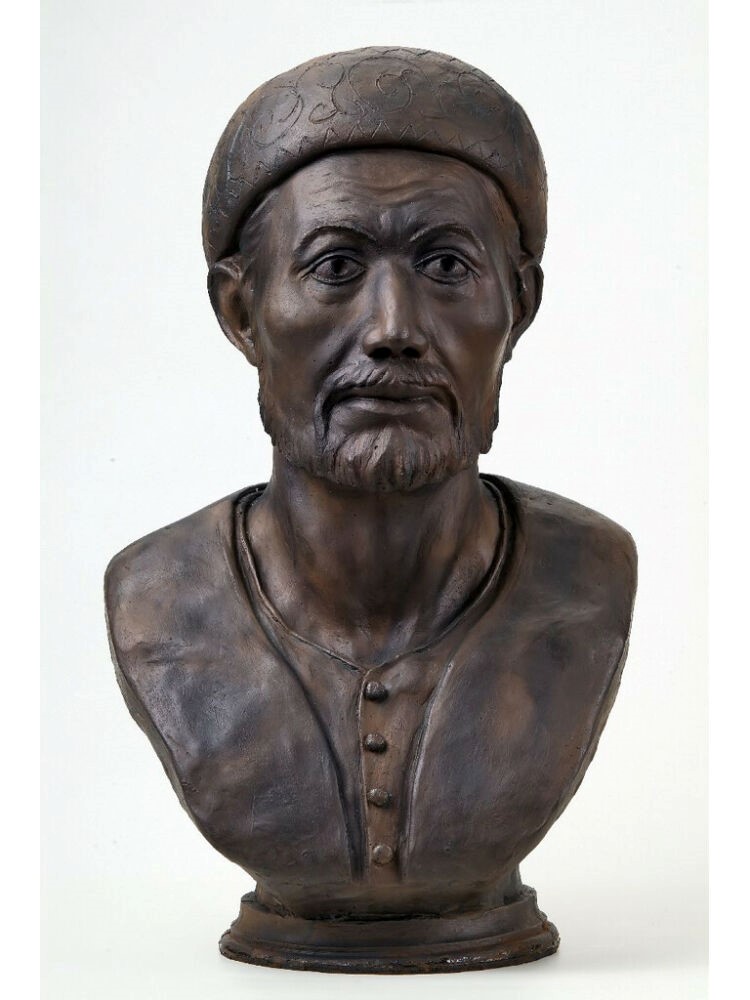

The historical work of the Volga-Ural Muslim scholar and Sufi,

Muhammad-Murad Ramzi al-Makki, entitled “Talfiq al-akhbar wa talqih al-athar fiwaqai Kazan wa Bulghar wa muluk at-tatar” contains a wealth of valuable data and significant observations. Being an enlightened Muslim, he devoted particular

attention to the history of Islam in the Volga region and the Cisurals. Of

considerable interest are the local legends he recounts, which explain why a number of Chuvash villages in the east of present-day Chuvashia bear Muslim names and why old cemeteries in some of them contain Muslim gravestones. It is important to note that in “Talfiq al-akhbar”, the term “Chuvash” carries a confessional, not an ethnic, meaning, denoting pagans as opposed to Muslims.

However, not all Tatar authors shared this view. The 19th-century local historian, Mingazutdin Dzhabali, believed that “in the era of the khans, all Chuvash were true Muslims of Khazar origin and true Turks, as evidenced by the grave markers in their abandoned cemeteries.”

“And even now, Islam has not taken firm root in the hearts of many of them due to their lack of proper knowledge of its truths, although in the recent past, there were among them those who knew them. Then, some of them began to adopt Christianity, if only outwardly. And so, enmity and hatred arose between those who had accepted Christianity and those who remained in Islam, or more precisely, between those among them who remained in idolatry and those who remained in Islam… This escalated into quarrels and brawls. Thus, Muslims began to move

away from those who had converted to Christianity and from the idolaters, resettling in areas where Muslims were strong and predominant. Moreover, the authorities mandated this very course. It reached the point that if three or four households in a large village accepted Christianity, then all remaining inhabitants were ordered either to likewise accept Christianity or to relocate elsewhere. As a result, many settlements were emptied of their Muslim inhabitants and became

Chuvash villages, whereas before, they had been Muslim. Among them are the villages of Adzhbaba (Izbebi), Kaval (Kovali), Urmary, Khodjasan

(Khozesanovo), Tikash (Tegeshevo), Shigali of the Tsivilsk Uyezd of Kazan

Governorate, as has already been mentioned in the first section of this book. In the same way, the villages of Baitiryak (Baiteryakovo), Dzhalshik (Bolshiye Yalchiki) and similar Chuvash villages belonging to the Tetushi uyezd of Kazan guberniya were indeed formerly Muslim villages and then became Chuvash, as is related among the inhabitants of those places. This is indicated by the presence of stones with Muslim inscriptions in the cemeteries of some of them, as was briefly mentioned at the beginning of the first section of this book. That these villages

were formerly Muslim is also indicated by the names of some of them. For example, the name of the village Khodjasan is undoubtedly a distorted rendering of the name KhodjaHasan, while now it is a Chuvash village in the upper reaches of the Kubnya river. It is known among the inhabitants of those places that the mosque of that village was moved to the village of Aydar located near the village of Arya Bakyrchysy (Bakyrche). The local imam, that is, the imam of the village

Arya Bakyrchysy, mullah AkhmedSafaEffendi, told me that he saw the mosque mentioned above in the village of Aydar when he had just arrived in the village of Arya Bakyrchysy as imam. Then, when it fell into decay, he rebuilt it, making it similar to the mosque from the village of Adzhbaba. Now, the village Adzhbaba, which today is Chuvash, is situated near the village of Akyeget (Akzigitovo). It (Adzhbaba) was originally a Muslim settlement called Hajji Baba. He was a man named Muhammad-Effendi. He served as a mudarris there, and after many years of teaching, he journeyed to the Hijaz to perform the hajj. Upon his return from the hajj, Sultan Suleiman Kanuni learned of him as a man distinguished by his knowledge and noble character. The Sultan appointed him as a mudarris in one of the madrasas of Istanbul, bestowed upon him the title of Chelebi, and he was addressed as “al-Hajj Chelebi Muhammad-Effendi”. After teaching there for several years, he felt a longing for his homeland. He returned and saw that the inhabitants of his native village had lapsed into ignorance, and many of them had

become Chuvash. Upon his return, he became known as Hajji Baba. It was from him that the village derived its name. Later, it was shortened to “Adjbaba”. And as his hour of death drew near, he bequeathed to his kin that they should bury him in the cemetery of the village of Arya Bakyrchysy, and they fulfilled his wish. This legend was related to me by the aforementioned Mullah Muhammad-Safa Effendi, who heard it from Mullah “Abd al-Nasir-Effendi al-Shirdani (the father of the enlightener Kayum Nasiri), who in turn had heard it from his teacher, Mullah Din-Muhammad-Effendi al-Bakyrji. And he said: “It was characteristic of him — that is, of Mullah Din-Muhammad — to possess perfect knowledge of oral histories.”

He further said: “I saw in the margins of the book “ar-Rawda”, which was copied for the aforementioned Mullah “Abd al-Nasir in 1855 CE, a note stating that the aforementioned Mullah Muhammad Effendi al-Celebi died in the year 939 AH (=3.08.1532 – 22.07.1533). And I, this humble one, visited his grave in the year 1316

AH (= 10.05.1898 – 28.04.1899) and saw upon it a large inscribed stone, but I could not decipher what was written thereon.”

It remains to add that the version of the legend reported by Murad Ramzi is given in the book “Татар халык иҗаты: Риваятьләр һәм легендалар” (Tatar folk

art: Traditions and legends)

Muhammad-Murad Ramzi al-Makki, entitled “Talfiq al-akhbar wa talqih al-athar fiwaqai Kazan wa Bulghar wa muluk at-tatar” contains a wealth of valuable data and significant observations. Being an enlightened Muslim, he devoted particular

attention to the history of Islam in the Volga region and the Cisurals. Of

considerable interest are the local legends he recounts, which explain why a number of Chuvash villages in the east of present-day Chuvashia bear Muslim names and why old cemeteries in some of them contain Muslim gravestones. It is important to note that in “Talfiq al-akhbar”, the term “Chuvash” carries a confessional, not an ethnic, meaning, denoting pagans as opposed to Muslims.

However, not all Tatar authors shared this view. The 19th-century local historian, Mingazutdin Dzhabali, believed that “in the era of the khans, all Chuvash were true Muslims of Khazar origin and true Turks, as evidenced by the grave markers in their abandoned cemeteries.”

“And even now, Islam has not taken firm root in the hearts of many of them due to their lack of proper knowledge of its truths, although in the recent past, there were among them those who knew them. Then, some of them began to adopt Christianity, if only outwardly. And so, enmity and hatred arose between those who had accepted Christianity and those who remained in Islam, or more precisely, between those among them who remained in idolatry and those who remained in Islam… This escalated into quarrels and brawls. Thus, Muslims began to move

away from those who had converted to Christianity and from the idolaters, resettling in areas where Muslims were strong and predominant. Moreover, the authorities mandated this very course. It reached the point that if three or four households in a large village accepted Christianity, then all remaining inhabitants were ordered either to likewise accept Christianity or to relocate elsewhere. As a result, many settlements were emptied of their Muslim inhabitants and became

Chuvash villages, whereas before, they had been Muslim. Among them are the villages of Adzhbaba (Izbebi), Kaval (Kovali), Urmary, Khodjasan

(Khozesanovo), Tikash (Tegeshevo), Shigali of the Tsivilsk Uyezd of Kazan

Governorate, as has already been mentioned in the first section of this book. In the same way, the villages of Baitiryak (Baiteryakovo), Dzhalshik (Bolshiye Yalchiki) and similar Chuvash villages belonging to the Tetushi uyezd of Kazan guberniya were indeed formerly Muslim villages and then became Chuvash, as is related among the inhabitants of those places. This is indicated by the presence of stones with Muslim inscriptions in the cemeteries of some of them, as was briefly mentioned at the beginning of the first section of this book. That these villages

were formerly Muslim is also indicated by the names of some of them. For example, the name of the village Khodjasan is undoubtedly a distorted rendering of the name KhodjaHasan, while now it is a Chuvash village in the upper reaches of the Kubnya river. It is known among the inhabitants of those places that the mosque of that village was moved to the village of Aydar located near the village of Arya Bakyrchysy (Bakyrche). The local imam, that is, the imam of the village

Arya Bakyrchysy, mullah AkhmedSafaEffendi, told me that he saw the mosque mentioned above in the village of Aydar when he had just arrived in the village of Arya Bakyrchysy as imam. Then, when it fell into decay, he rebuilt it, making it similar to the mosque from the village of Adzhbaba. Now, the village Adzhbaba, which today is Chuvash, is situated near the village of Akyeget (Akzigitovo). It (Adzhbaba) was originally a Muslim settlement called Hajji Baba. He was a man named Muhammad-Effendi. He served as a mudarris there, and after many years of teaching, he journeyed to the Hijaz to perform the hajj. Upon his return from the hajj, Sultan Suleiman Kanuni learned of him as a man distinguished by his knowledge and noble character. The Sultan appointed him as a mudarris in one of the madrasas of Istanbul, bestowed upon him the title of Chelebi, and he was addressed as “al-Hajj Chelebi Muhammad-Effendi”. After teaching there for several years, he felt a longing for his homeland. He returned and saw that the inhabitants of his native village had lapsed into ignorance, and many of them had

become Chuvash. Upon his return, he became known as Hajji Baba. It was from him that the village derived its name. Later, it was shortened to “Adjbaba”. And as his hour of death drew near, he bequeathed to his kin that they should bury him in the cemetery of the village of Arya Bakyrchysy, and they fulfilled his wish. This legend was related to me by the aforementioned Mullah Muhammad-Safa Effendi, who heard it from Mullah “Abd al-Nasir-Effendi al-Shirdani (the father of the enlightener Kayum Nasiri), who in turn had heard it from his teacher, Mullah Din-Muhammad-Effendi al-Bakyrji. And he said: “It was characteristic of him — that is, of Mullah Din-Muhammad — to possess perfect knowledge of oral histories.”

He further said: “I saw in the margins of the book “ar-Rawda”, which was copied for the aforementioned Mullah “Abd al-Nasir in 1855 CE, a note stating that the aforementioned Mullah Muhammad Effendi al-Celebi died in the year 939 AH (=3.08.1532 – 22.07.1533). And I, this humble one, visited his grave in the year 1316

AH (= 10.05.1898 – 28.04.1899) and saw upon it a large inscribed stone, but I could not decipher what was written thereon.”

It remains to add that the version of the legend reported by Murad Ramzi is given in the book “Татар халык иҗаты: Риваятьләр һәм легендалар” (Tatar folk

art: Traditions and legends)