Turkish Accounts of Festival Prayers in St. Petersburg, 1890–1891

It is well known that Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who occupied the Ottoman throne from 1876 to 1909, positioned himself more explicitly than his predecessors as the Caliph—the “Successor to the Prophet Muhammad on Earth.” Undoubtedly, this posture influenced the foreign policy of the Ottoman Empire, encouraging it, if not to directly intervene in the affairs of states with Muslim populations, then at least to closely monitor the condition of their Muslim subjects.

It is precisely within this context that we should consider the following reports from two officials of the Turkish embassy in Russia: the Fifth Secretary, Abdürrezzak, and the First Secretary, Seyyid Abdulbaki, who attended the festival prayers of the Muslim community in St. Petersburg. The services they described were held for the Festival of Fast-Breaking (Arabic: `Eid al-Fitr`, Tatar: Uraza Bayrame) in 1890 and 1891, respectively. Their dispatches contain information of historical, religious, and even ethnographic value, alongside attempts to analyze the standing of Russia’s Muslims.

The Ottoman officials paid considerable attention not only to differences in the performance of religious rites between Ottoman and Russian Muslim practice but also to the latter’s physical appearance. The scene they witnessed led them to conclude that Russian Muslims lived in conditions that fostered an “elementary forgetfulness” of their religion.

Strictly speaking, the order of the festival prayers they observed in St. Petersburg (despite the criticisms raised by Abdürrezzak and, particularly, Abdulbaki) did not contravene the canonical norms of the Hanafi school of law. Contrary to Abdulbaki’s presumption, the manner of delivering the sermon (khutbah) he witnessed was not intentionally altered to placate the Russian administration. It appears that only the absence of the loud glorification of Allah (takbir) might be attributed to official pressure. From a Hanafi perspective, however, a quiet or silent takbir is entirely permissible when conditions are not conducive to its loud proclamation.

Regarding the St. Petersburg imam’s use of the modest title “Commanders of the Faithful” for the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, as noted by Abdulbaki, his suggestion that this stemmed from the Russian government’s irritation with the canonical title “True Successor of the Messenger of Allah” is similarly unfounded. It was far more likely a local Muslim convention.

The attire and appearance of the “Tatar Muslims” living in St. Petersburg, who were dressed according to European fashion, proved no less startling to the Ottoman diplomats. “The majority of them (the Muslims who came to worship – I.M.) wore a skullcap, with a hat placed beside them; some were clean-shaven, others had only shaved their mustaches, and some sported forked beards—in short, they exhibited the same inappropriate [for Muslims] appearance we observe among Europeans,” wrote Abdürrezzak. “Their appearance was such that one might mistake them for Russians,” echoed Abdulbaki.

European clothing, (especially hats), was traditionally viewed by Ottomans as a marker of the “enemies of the faith.” Abdürrezzak Bey was further displeased by the seemingly frivolous attitude these “unfortunate Russian Muslims” held towards their own appearance and person (which likely explains why Abdulbaki, attending the prayer the following year, chose not to stand out and wore a Tatar skullcap). Abdürrezzak also could not resist a sarcastic remark concerning the “retired General Genghis Khan and ‘scions of khans'” who earned their living running restaurants—an occupation deemed far from prestigious in the eyes of an educated Ottoman.

These Turkish diplomats could only judge the state of Russia’s Muslims by the residents of the imperial capital. The Muslims of Moscow and St. Petersburg lived dispersed and were highly integrated into Russian society. In contrast, throughout the Volga-Ural region and Siberia, Muslim populations typically resided in distinct villages or urban quarters (in cities), preserving their traditional way of life for a long time. Consequently, Abdulbaki’s conviction that the conduct of the festival prayer in St. Petersburg was indicative of a broader state policy towards Muslims, or reflective of their true condition, appears highly simplistic. This is especially true given that, as revealed in Abdürrezzak’s report, the Turkish embassy staff had not previously attended any festival prayers organized by the St. Petersburg community.

Another reason for the Turkish diplomats’ keen interest in the religious life of St. Petersburg’s Muslims was undoubtedly the project to build a cathedral mosque in the city. Official permission to collect donations had been secured in 1883, following repeated petitions from authorized representatives of the St. Petersburg Muslim community and from the Orenburg Mufti, Selimgirey Tevkelev[1] himself.

Ahund Ataulla Bayazitov[2] was appointed the chief trustee for fundraising. Although donations were solicited throughout the jurisdiction of the Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly, progress was slow. The construction of a cathedral mosque in the Russian capital implied that it would become the principal site of Muslim worship in the empire. It was likely for this reason that news of the proposed mosque attracted the personal attention of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and prompted the Ottoman elite to consider offering financial support. While it remains unknown whether the Porte ultimately provided substantial aid, the importance attached to the matter in Istanbul is evident from the instructions given to Kamil Pasha, a high-ranking official in the sultan’s chancery. During his two visits to Russia (in 1895 and 1896), alongside his diplomatic duties, he was tasked with gathering information on the funds required for the St. Petersburg mosque’s construction. The embassy officials’ reports, which emphasized that prayers were held in unsuitable venues under conditions contrary to Sharia stipulations, seemingly reinforced the Padishah’s conviction of the necessity to assist St. Petersburg’s Muslims in building a proper mosque.

The original documents are held in the Ottoman Archives (Istanbul).

Documents

No. 1

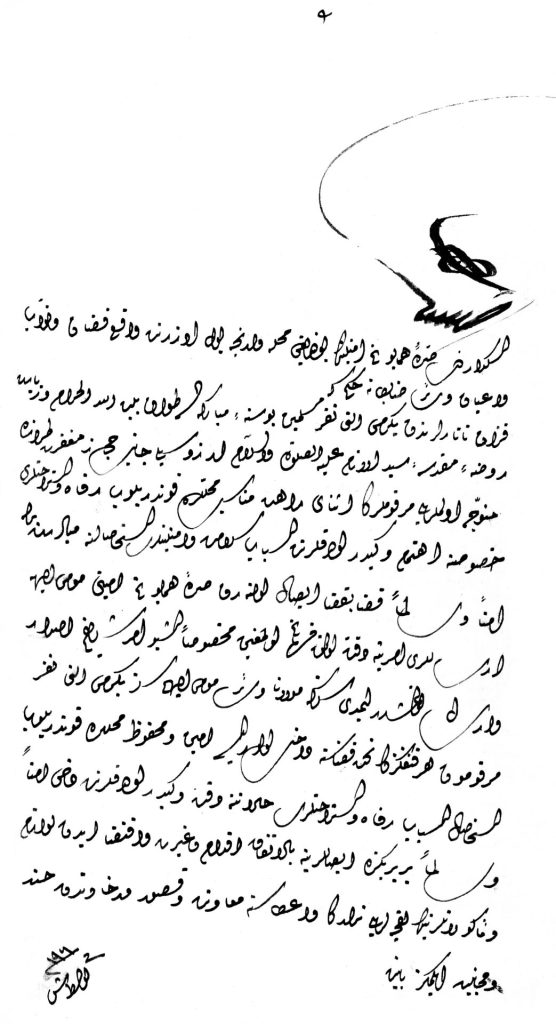

May 19, 1890 — From the report of the Third Secretary of the Ottoman Embassy in St. Petersburg, Abdürrezzak, to the Sultan’s Aide-de-Camp, Dervish Pasha.

…Thus, Your humble servant, from the moment of my arrival in St. Petersburg until now, has not only diligently sought to understand these circumstances but, in fulfillment of my religious duties, also participated in the festival prayer during the recent Festival of Fast-Breaking[3]. As there is no mosque here, and the venue designated for the prayer was the hall of the City Duma (Belediye salonu)[4], I met with the local Tatar imam, Ataullah Efendi, and informed him of my intention. The imam, remarking with some reproach that until now no one from our embassy had ever attended [worship services], expressed great joy and added that he would prepare a place for me in the first row [of worshippers].

On the morning of the festival, I specially ordered an ornate carriage and proceeded to the prayer venue. Ascending a long staircase and passing a great number of beggars and women dressed in a manner non-compliant with Islamic norms—both Muslim men and women—I entered the hall where the prayer was to be held. In truth, the initial impression was staggering. On the qibla side of the hall hung large veiled portraits, alongside other very large ones: on the right, an unveiled portrait of the reigning Emperor; behind, portraits of the deceased Emperors Alexander II, Nicholas[5] and various Empresses, with crosses depicted upon their heads. Also incongruous was the sight, on the left, of what the French call a “chapelle”: an assemblage of images of Jesus, Mary, and other figures venerated by Christians, before which a lamp burned[6]. The sight of some seven or eight hundred Muslims standing in rows there would astonish any observer. Most wore a skullcap, with a hat placed nearby; some were clean-shaven, others had shaved only their mustaches, and some had forked beards—in short, the same inappropriate [for Muslims] appearance we observe among Europeans. Equally astonishing was the spectacle of more than two hundred men in hats, standing together in one part of this makeshift mosque, that is, the hall. When they saw someone entering in an Ottoman fez and frock coat, people began questioning my servant about me, their faces betraying expressions of unwarranted amusement. The imam recited several hadiths concerning the virtues of sadaqat al-fitr[7], then came forward and delivered a sermon in the Tatar-Turkish dialect (which I understood perfectly) on the importance of neatness in dress. Thereafter, taking a long staff in hand, he climbed onto his bench using two planks that served as steps for the improvised minbar, and recited the khutbah. Having mentioned the sacred names of the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs and recited several well-known Quranic verses, he concluded the khutbah with the phrase, “Let us also pray for the success and health of our Sovereign Alexander III, his heir-apparent Tsarevich Nicholas, and his honorable spouse,” after which the prayer was performed. Then, after the imam introduced Your humble servant to the retired General Genghis Khan[8] and numerous other “scions of khans” who manage restaurants, the congregation dispersed. Your humble servant, while descending the staircase, distributed all the money I had on my person as alms to the aforementioned beggars, for the sake of the crown of His Imperial Majesty, the Caliph. […].

While there is no cause to doubt the personal piety of Imam Ataullah Efendi, it must be noted that he was educated in a Russian school, receives a lawful salary from the Russian government, and has been granted a civil rank equivalent to the Ottoman rank of first-class civil servant (ūlā rütbesi)[9]. The local Muslims are aware that Ataullah Efendi, with his hat and official uniform, has, in effect, ‘gone over to the Russians’[10], and many hold this against him. […]

No. 2

1 Shawwal 1308 A.H. = April 28, 1891 A.D. — From the report of the First Secretary of the Ottoman Embassy in St. Petersburg, Seyyid Abdulbaki, addressed to the Sultan.

…As detailed in my previously submitted memorandum (lâyiha), the absence of a mosque in St. Petersburg means the five daily prayers are conducted in various private premises.[11]. For the festival prayers, however, owing to the larger number of worshippers, the Russian government designates two or three locations—ostensibly to demonstrate goodwill towards Muslims, but in reality, to supervise and control the assembled crowd. The most significant of these venues is the hall of the St. Petersburg City Duma [12]. Having heard that a great many believers gathered there, I chose to attend. Considering that my fez would draw unwanted attention and hinder my observations, I donned a Tatar cap (Tatar kalpağı) to remain inconspicuous and proceeded to the said location. Upon arriving at the doors [of the hall], I saw men in hats arriving. Their appearance was such that one might mistake them for Russians, and I was surprised to hear them exchanging greetings in the Muslim fashion. Some of them, upon entering, left their hats with the doorkeeper, pulled skullcaps and caps (takke ve kalpak) from their pockets, and put them on; others, however, went upstairs still wearing their hats, which I found utterly astonishing. Eventually, this insignificant one also ascended and entered the large hall serving as the place of worship. Although the furniture in this hall, normally used for grand receptions and city council meetings, had been pushed to one side to clear space for worshippers, five or six very large oil paintings remained hanging on the walls. Only those on the qibla side had been covered with cloth; those on the sides and to the rear of the congregation were left exposed. The veiled paintings on the qibla wall still displayed cross-shaped finials at their tops. The uncovered portraits depicted life-size images of the current Emperor Alexander III, one of his venerated ancestors, Alexander I, and his father, Alexander II. Having surveyed the walls of this hall, which more closely resembled a museum, or indeed a church, I turned my attention to the assembled Muslims. They numbered around three hundred. Some wore turbans, others skullcaps or caps, but there were also those who had kept their hats on. Upon the bare planks of the polished floor—highly suitable for dancing—the attendees spread white sheets they had brought with them to serve as prayer rugs. On the qibla side, a two-step ladder served as the minbar. Throughout the Ottoman domains, it is customary for the faithful gathered in mosques for the festival prayer to recite the takbir in unison at intervals. Here, however, the Muslims stood in utter silence, like accused men in a courtroom, and the majority of those present seemed wholly unacquainted with the [proper] etiquette and customs of performing religious rites. […]

Ataullah Efendi Bayazidov, with whom I had previously conversed as reported, proceeded to the mihrab. The prayer was performed in silence, without the loud takbirs that normally accompany it, called out by a muezzin. Following this, the imam ascended the ladder serving as the minbar and recited the khutbah. Several aspects of it drew my attention. Firstly, when mentioning the names of the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs, he applied the phrase “the True Successor of the Messenger of Allah” (Halîfetü Rasulullahi ale’t-tahkîk) to none of them, contenting himself instead with the title “Commanders of the Faithful” (Emîrü’l-mü’minîn). It is highly probable that this departure from tradition, referring to the Caliphs merely as “Commanders of the Faithful,” is due to the Russian government’s irritation with the canonical title “Successor of the Messenger of Allah” (Halîfe-i Rasulullah), rather than being an established custom among the Tatars. After concluding the khutba, the preacher (khatib) delivered a sermon (va’z) in the Tatar language, offered several prayers for the Tsar, and then descended from the minbar. The presence of these, along with other minor deviations from the khutbahs recited in the Ottoman State, suggests that the text was either censored by the Russian government or that the Tatars themselves altered its content to avoid provoking displeasure. The fact that the khatib delivered the sermon, which was essentially a prayer for the Tsar, from the minbar itself and solely in Turkic, seems specifically intended to dissociate the canonical khutbah from the subsequent prayer for the tsar.

Firmly believing that the observations I have detailed above will enable conclusions to be drawn regarding the condition of Russia’s Muslims, I venture to submit them, along with a clipping from a recent article published in the St. Petersburg newspaper Novoye Vremya—a response to Ataullah Efendi’s reddiye[13] —which I attach to my most humble memorandum, to the Exalted Threshold.

Source: Documents on the History of the Volga-Ural Region from the 16th to the 19th Centuries from Turkish Repositories: A Collection of Documents / Comp. I. A. Mustakimov; under the general editorship of D. I. Ibragimov. — Kazan: Gasyr, 2008.

[1] Tevkelev, Selimgirey (Mufti 1865–1885) — The fourth Mufti of the Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly.

[2] Bayazitov, Ataulla (1847–1911) — Religious and public figure, publicist, publisher. Imam of the 2nd Muslim parish in St. Petersburg, Ahund, translator and lecturer for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[3] The Festival of Fast-Breaking, celebrated on 1 Shawwal, fell on May 9 (Julian Calendar) in 1890.

[4] Presumably the Alexandrovsky Hall of the St. Petersburg City Duma.

[5] Referring to Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855).

[6] Clearly a reference to an iconostasis (one meaning of the French word chapelle)

[7] The obligatory (wājib) alms given during Ramadan, amounting to one sa’ (approx. 3.272 kg) of wheat. (See: Al-Hidaya: Commentary on Islamic Law. — Tashkent, 1994. — Pp. 118–120).

[8] Apparently, Lieutenant General Sultan Haji Gubaydulla Jangir-ogly Chingis-Khan (1840–?), son of Jangir Khan, ruler of the Bukey Horde. An active member of St. Petersburg’s Muslim community and later a member of the “Committee for the Construction of the Cathedral Mosque in St. Petersburg” formed in 1906.

[9] Ûlâ rütbesi, rütbe-i ûlâ – civil rank in the Ottoman table of ranks (Tsvetkov P. Turkish–Russian dictionary. – St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 146). It was not possible to establish which Russian rank he corresponded to.

[10] I.e., had assimilated into Russian official society, which the author of the document contrasted with the Muslim community of the empire.

[11] In the 19th century, private imams’ apartments were used to perform prayers (mostly on Fridays). On religious holidays, special rooms were rented (the hall of the Noble Assembly, the Alexander Hall of the City Duma, the Horse Guards Manege, the Provincial Land Administration, etc.).

[12] Apparently, this refers to the Alexander Hall of the City Duma of St. Petersburg.

[13] Reddiye — A polemical treatise defending Islam, typically written in response to criticisms from Christian missionaries or scholars.

It is precisely within this context that we should consider the following reports from two officials of the Turkish embassy in Russia: the Fifth Secretary, Abdürrezzak, and the First Secretary, Seyyid Abdulbaki, who attended the festival prayers of the Muslim community in St. Petersburg. The services they described were held for the Festival of Fast-Breaking (Arabic: `Eid al-Fitr`, Tatar: Uraza Bayrame) in 1890 and 1891, respectively. Their dispatches contain information of historical, religious, and even ethnographic value, alongside attempts to analyze the standing of Russia’s Muslims.

The Ottoman officials paid considerable attention not only to differences in the performance of religious rites between Ottoman and Russian Muslim practice but also to the latter’s physical appearance. The scene they witnessed led them to conclude that Russian Muslims lived in conditions that fostered an “elementary forgetfulness” of their religion.

Strictly speaking, the order of the festival prayers they observed in St. Petersburg (despite the criticisms raised by Abdürrezzak and, particularly, Abdulbaki) did not contravene the canonical norms of the Hanafi school of law. Contrary to Abdulbaki’s presumption, the manner of delivering the sermon (khutbah) he witnessed was not intentionally altered to placate the Russian administration. It appears that only the absence of the loud glorification of Allah (takbir) might be attributed to official pressure. From a Hanafi perspective, however, a quiet or silent takbir is entirely permissible when conditions are not conducive to its loud proclamation.

Regarding the St. Petersburg imam’s use of the modest title “Commanders of the Faithful” for the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, as noted by Abdulbaki, his suggestion that this stemmed from the Russian government’s irritation with the canonical title “True Successor of the Messenger of Allah” is similarly unfounded. It was far more likely a local Muslim convention.

The attire and appearance of the “Tatar Muslims” living in St. Petersburg, who were dressed according to European fashion, proved no less startling to the Ottoman diplomats. “The majority of them (the Muslims who came to worship – I.M.) wore a skullcap, with a hat placed beside them; some were clean-shaven, others had only shaved their mustaches, and some sported forked beards—in short, they exhibited the same inappropriate [for Muslims] appearance we observe among Europeans,” wrote Abdürrezzak. “Their appearance was such that one might mistake them for Russians,” echoed Abdulbaki.

European clothing, (especially hats), was traditionally viewed by Ottomans as a marker of the “enemies of the faith.” Abdürrezzak Bey was further displeased by the seemingly frivolous attitude these “unfortunate Russian Muslims” held towards their own appearance and person (which likely explains why Abdulbaki, attending the prayer the following year, chose not to stand out and wore a Tatar skullcap). Abdürrezzak also could not resist a sarcastic remark concerning the “retired General Genghis Khan and ‘scions of khans'” who earned their living running restaurants—an occupation deemed far from prestigious in the eyes of an educated Ottoman.

These Turkish diplomats could only judge the state of Russia’s Muslims by the residents of the imperial capital. The Muslims of Moscow and St. Petersburg lived dispersed and were highly integrated into Russian society. In contrast, throughout the Volga-Ural region and Siberia, Muslim populations typically resided in distinct villages or urban quarters (in cities), preserving their traditional way of life for a long time. Consequently, Abdulbaki’s conviction that the conduct of the festival prayer in St. Petersburg was indicative of a broader state policy towards Muslims, or reflective of their true condition, appears highly simplistic. This is especially true given that, as revealed in Abdürrezzak’s report, the Turkish embassy staff had not previously attended any festival prayers organized by the St. Petersburg community.

Another reason for the Turkish diplomats’ keen interest in the religious life of St. Petersburg’s Muslims was undoubtedly the project to build a cathedral mosque in the city. Official permission to collect donations had been secured in 1883, following repeated petitions from authorized representatives of the St. Petersburg Muslim community and from the Orenburg Mufti, Selimgirey Tevkelev[1] himself.

Ahund Ataulla Bayazitov[2] was appointed the chief trustee for fundraising. Although donations were solicited throughout the jurisdiction of the Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly, progress was slow. The construction of a cathedral mosque in the Russian capital implied that it would become the principal site of Muslim worship in the empire. It was likely for this reason that news of the proposed mosque attracted the personal attention of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and prompted the Ottoman elite to consider offering financial support. While it remains unknown whether the Porte ultimately provided substantial aid, the importance attached to the matter in Istanbul is evident from the instructions given to Kamil Pasha, a high-ranking official in the sultan’s chancery. During his two visits to Russia (in 1895 and 1896), alongside his diplomatic duties, he was tasked with gathering information on the funds required for the St. Petersburg mosque’s construction. The embassy officials’ reports, which emphasized that prayers were held in unsuitable venues under conditions contrary to Sharia stipulations, seemingly reinforced the Padishah’s conviction of the necessity to assist St. Petersburg’s Muslims in building a proper mosque.

The original documents are held in the Ottoman Archives (Istanbul).

Documents

No. 1

May 19, 1890 — From the report of the Third Secretary of the Ottoman Embassy in St. Petersburg, Abdürrezzak, to the Sultan’s Aide-de-Camp, Dervish Pasha.

…Thus, Your humble servant, from the moment of my arrival in St. Petersburg until now, has not only diligently sought to understand these circumstances but, in fulfillment of my religious duties, also participated in the festival prayer during the recent Festival of Fast-Breaking[3]. As there is no mosque here, and the venue designated for the prayer was the hall of the City Duma (Belediye salonu)[4], I met with the local Tatar imam, Ataullah Efendi, and informed him of my intention. The imam, remarking with some reproach that until now no one from our embassy had ever attended [worship services], expressed great joy and added that he would prepare a place for me in the first row [of worshippers].

On the morning of the festival, I specially ordered an ornate carriage and proceeded to the prayer venue. Ascending a long staircase and passing a great number of beggars and women dressed in a manner non-compliant with Islamic norms—both Muslim men and women—I entered the hall where the prayer was to be held. In truth, the initial impression was staggering. On the qibla side of the hall hung large veiled portraits, alongside other very large ones: on the right, an unveiled portrait of the reigning Emperor; behind, portraits of the deceased Emperors Alexander II, Nicholas[5] and various Empresses, with crosses depicted upon their heads. Also incongruous was the sight, on the left, of what the French call a “chapelle”: an assemblage of images of Jesus, Mary, and other figures venerated by Christians, before which a lamp burned[6]. The sight of some seven or eight hundred Muslims standing in rows there would astonish any observer. Most wore a skullcap, with a hat placed nearby; some were clean-shaven, others had shaved only their mustaches, and some had forked beards—in short, the same inappropriate [for Muslims] appearance we observe among Europeans. Equally astonishing was the spectacle of more than two hundred men in hats, standing together in one part of this makeshift mosque, that is, the hall. When they saw someone entering in an Ottoman fez and frock coat, people began questioning my servant about me, their faces betraying expressions of unwarranted amusement. The imam recited several hadiths concerning the virtues of sadaqat al-fitr[7], then came forward and delivered a sermon in the Tatar-Turkish dialect (which I understood perfectly) on the importance of neatness in dress. Thereafter, taking a long staff in hand, he climbed onto his bench using two planks that served as steps for the improvised minbar, and recited the khutbah. Having mentioned the sacred names of the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs and recited several well-known Quranic verses, he concluded the khutbah with the phrase, “Let us also pray for the success and health of our Sovereign Alexander III, his heir-apparent Tsarevich Nicholas, and his honorable spouse,” after which the prayer was performed. Then, after the imam introduced Your humble servant to the retired General Genghis Khan[8] and numerous other “scions of khans” who manage restaurants, the congregation dispersed. Your humble servant, while descending the staircase, distributed all the money I had on my person as alms to the aforementioned beggars, for the sake of the crown of His Imperial Majesty, the Caliph. […].

While there is no cause to doubt the personal piety of Imam Ataullah Efendi, it must be noted that he was educated in a Russian school, receives a lawful salary from the Russian government, and has been granted a civil rank equivalent to the Ottoman rank of first-class civil servant (ūlā rütbesi)[9]. The local Muslims are aware that Ataullah Efendi, with his hat and official uniform, has, in effect, ‘gone over to the Russians’[10], and many hold this against him. […]

No. 2

1 Shawwal 1308 A.H. = April 28, 1891 A.D. — From the report of the First Secretary of the Ottoman Embassy in St. Petersburg, Seyyid Abdulbaki, addressed to the Sultan.

…As detailed in my previously submitted memorandum (lâyiha), the absence of a mosque in St. Petersburg means the five daily prayers are conducted in various private premises.[11]. For the festival prayers, however, owing to the larger number of worshippers, the Russian government designates two or three locations—ostensibly to demonstrate goodwill towards Muslims, but in reality, to supervise and control the assembled crowd. The most significant of these venues is the hall of the St. Petersburg City Duma [12]. Having heard that a great many believers gathered there, I chose to attend. Considering that my fez would draw unwanted attention and hinder my observations, I donned a Tatar cap (Tatar kalpağı) to remain inconspicuous and proceeded to the said location. Upon arriving at the doors [of the hall], I saw men in hats arriving. Their appearance was such that one might mistake them for Russians, and I was surprised to hear them exchanging greetings in the Muslim fashion. Some of them, upon entering, left their hats with the doorkeeper, pulled skullcaps and caps (takke ve kalpak) from their pockets, and put them on; others, however, went upstairs still wearing their hats, which I found utterly astonishing. Eventually, this insignificant one also ascended and entered the large hall serving as the place of worship. Although the furniture in this hall, normally used for grand receptions and city council meetings, had been pushed to one side to clear space for worshippers, five or six very large oil paintings remained hanging on the walls. Only those on the qibla side had been covered with cloth; those on the sides and to the rear of the congregation were left exposed. The veiled paintings on the qibla wall still displayed cross-shaped finials at their tops. The uncovered portraits depicted life-size images of the current Emperor Alexander III, one of his venerated ancestors, Alexander I, and his father, Alexander II. Having surveyed the walls of this hall, which more closely resembled a museum, or indeed a church, I turned my attention to the assembled Muslims. They numbered around three hundred. Some wore turbans, others skullcaps or caps, but there were also those who had kept their hats on. Upon the bare planks of the polished floor—highly suitable for dancing—the attendees spread white sheets they had brought with them to serve as prayer rugs. On the qibla side, a two-step ladder served as the minbar. Throughout the Ottoman domains, it is customary for the faithful gathered in mosques for the festival prayer to recite the takbir in unison at intervals. Here, however, the Muslims stood in utter silence, like accused men in a courtroom, and the majority of those present seemed wholly unacquainted with the [proper] etiquette and customs of performing religious rites. […]

Ataullah Efendi Bayazidov, with whom I had previously conversed as reported, proceeded to the mihrab. The prayer was performed in silence, without the loud takbirs that normally accompany it, called out by a muezzin. Following this, the imam ascended the ladder serving as the minbar and recited the khutbah. Several aspects of it drew my attention. Firstly, when mentioning the names of the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs, he applied the phrase “the True Successor of the Messenger of Allah” (Halîfetü Rasulullahi ale’t-tahkîk) to none of them, contenting himself instead with the title “Commanders of the Faithful” (Emîrü’l-mü’minîn). It is highly probable that this departure from tradition, referring to the Caliphs merely as “Commanders of the Faithful,” is due to the Russian government’s irritation with the canonical title “Successor of the Messenger of Allah” (Halîfe-i Rasulullah), rather than being an established custom among the Tatars. After concluding the khutba, the preacher (khatib) delivered a sermon (va’z) in the Tatar language, offered several prayers for the Tsar, and then descended from the minbar. The presence of these, along with other minor deviations from the khutbahs recited in the Ottoman State, suggests that the text was either censored by the Russian government or that the Tatars themselves altered its content to avoid provoking displeasure. The fact that the khatib delivered the sermon, which was essentially a prayer for the Tsar, from the minbar itself and solely in Turkic, seems specifically intended to dissociate the canonical khutbah from the subsequent prayer for the tsar.

Firmly believing that the observations I have detailed above will enable conclusions to be drawn regarding the condition of Russia’s Muslims, I venture to submit them, along with a clipping from a recent article published in the St. Petersburg newspaper Novoye Vremya—a response to Ataullah Efendi’s reddiye[13] —which I attach to my most humble memorandum, to the Exalted Threshold.

Source: Documents on the History of the Volga-Ural Region from the 16th to the 19th Centuries from Turkish Repositories: A Collection of Documents / Comp. I. A. Mustakimov; under the general editorship of D. I. Ibragimov. — Kazan: Gasyr, 2008.

[1] Tevkelev, Selimgirey (Mufti 1865–1885) — The fourth Mufti of the Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly.

[2] Bayazitov, Ataulla (1847–1911) — Religious and public figure, publicist, publisher. Imam of the 2nd Muslim parish in St. Petersburg, Ahund, translator and lecturer for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[3] The Festival of Fast-Breaking, celebrated on 1 Shawwal, fell on May 9 (Julian Calendar) in 1890.

[4] Presumably the Alexandrovsky Hall of the St. Petersburg City Duma.

[5] Referring to Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855).

[6] Clearly a reference to an iconostasis (one meaning of the French word chapelle)

[7] The obligatory (wājib) alms given during Ramadan, amounting to one sa’ (approx. 3.272 kg) of wheat. (See: Al-Hidaya: Commentary on Islamic Law. — Tashkent, 1994. — Pp. 118–120).

[8] Apparently, Lieutenant General Sultan Haji Gubaydulla Jangir-ogly Chingis-Khan (1840–?), son of Jangir Khan, ruler of the Bukey Horde. An active member of St. Petersburg’s Muslim community and later a member of the “Committee for the Construction of the Cathedral Mosque in St. Petersburg” formed in 1906.

[9] Ûlâ rütbesi, rütbe-i ûlâ – civil rank in the Ottoman table of ranks (Tsvetkov P. Turkish–Russian dictionary. – St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 146). It was not possible to establish which Russian rank he corresponded to.

[10] I.e., had assimilated into Russian official society, which the author of the document contrasted with the Muslim community of the empire.

[11] In the 19th century, private imams’ apartments were used to perform prayers (mostly on Fridays). On religious holidays, special rooms were rented (the hall of the Noble Assembly, the Alexander Hall of the City Duma, the Horse Guards Manege, the Provincial Land Administration, etc.).

[12] Apparently, this refers to the Alexander Hall of the City Duma of St. Petersburg.

[13] Reddiye — A polemical treatise defending Islam, typically written in response to criticisms from Christian missionaries or scholars.